Colonial Houses

It is well worth while for us at this point to look more in detail at

the colonial towns to see the houses in which our ancestors dwelt and to

note the architecture of their public edifices, for these men had a

distinctive style of building as characteristic of their age as

skyscrapers and apartment houses are of the present century. The household

furnishings have also a charm of their own and in many cases, by their

combination of utility and good taste, have provided models for the

craftsmen of a later day. A brief survey of colonial houses, inside and

out, will serve to give us a much clearer idea of the environment in which

the people lived during the colonial era.

The materials used by the colonists for building were wood, brick, and

more rarely stone. At first practically all houses were of wood, as was

natural in a country where this material lay ready to every man's hand and

where the means for making brick or cutting stone were not readily

accessible. Clay, though early used for chimneys, was not substantial

enough for house building, and lime for mortar

and plaster was not easy to obtain. Though limestone was discovered in New

England in 1697, it was not known at all in the tidewater section of the

South, where lime continued to the end of the era to be made from calcined

oyster shells. The seventeenth century was the period of wooden houses,

wooden churches, and wooden public buildings; it was the eighteenth

century which saw the erection of brick buildings in America.

Up to the time of the Revolution bricks were brought from England and

Holland, and are found entered in cargo lists as late as 1770, though they

probably served often only as ballast. But most of the bricks used in

colonial buildings were molded and burnt in America. There were brick

kilns everywhere in the colonies from Portsmouth to Savannah.

Indeed bricks were made, north and south, in large enough quantities to be

exported yearly to the West Indies. As building stone scarcely existed in

the South, all important buildings there were of brick, or in case greater

strength were needed, as for Fort Johnston at the mouth of the Cape Fear

River or the fortifications of Charleston, of tappy work, a mixture of

concrete and shells. Brick walls were often built very thick; those of St.

Philip's Church, Brunswick, still show three feet in depth. Chimneys were

heavy, often in stacks, and windows as a rule were small. The bonding was

English, Flemish, or "running," according to the taste of the builder, and

many of the houses had stone trimming, which had to be brought from

England, if it were of freestone as was suggested for King's Chapel,

Boston, or of marble as in Governor Tryon's palace in New Bern.

Buildings of stone were not common and were confined chiefly to the North,

where this material could be easily and cheaply obtained. As early as 1639

Henry Whitfield erected a house of stone at Guilford, Connecticut, to

serve in part as a place of defense, and in other places, here and there,

were to be found stone buildings used for various purposes. It has been

said that King's Chapel, Boston, built in 1749-54, was the first building

in America to be constructed of hewn stone, but this is not the case. Some

of the early houses in New York as well as the two Anglican churches were

of hewn stone. The Malbone country house near Newport, built before 1750,

was also "of hewn stone and all the corners and sides of the windows

painted to represent marble. " There were many houses in the colonies

painted to resemble stone, and some in which only the first story or the

basement was of this material, while in many instances there were broad

stone steps leading up to a house otherwise constructed of wood or brick.

Stone for building purposes was therefore well known and frequently used.

Travelers who visited the leading towns in the period from 1750 to 1763

have left descriptions which help us to visualize the external features of

these places. Portsmouth, the most northerly town of importance, had

houses of both wood and brick, "large and exceeding neat," we are told,

"generally 3 story high and well sashed and glazed with the best glass,

the rooms well plastered and many wainscoted or hung with painted paper

from England, the outside clapboarded very neatly." Salem was "a large

town well built, many genteel large houses (which tho' of wood) are all

planed and painted on the outside in imitation

of hewn stone." By 1750 Boston had about three thousand houses and twenty

thousand inhabitants; two-thirds of the houses were of wood, two or three

stories high, mostly sashed, the remainder of brick, substantially built

and in excellent architectural taste. The streets were well paved with

stone, a thing rare in New England, but those in the North End were

crooked, narrow, and disagreeable. Worcester was "one of the best built

and prettiest inland little towns" that Lord Adam Gordon had seen in

America. The houses in Newport, with one or two exceptions, were of wood,

making "a good appearance and also as well furnished as in most places you

will meet with, many of the rooms being hung with printed canvas and

paper, which looks very neat, others are well wainscoted and painted. "

New London with its one street a mile long by the river side and its

houses built of wood, seemed in 1750 to be "new and neat. " New Haven,

which covered a great deal of ground, was laid out in nine squares around

a green or market place, and contained many houses in wood, a few in brick

or stone, a brick statehouse, a brick meetinghouse, and Yale College,

which was being rebuilt in brick. Middletown, though one of the most

important commercial centers between New York and Boston and the third

town in Connecticut, had only wooden houses. Hartford, "a large,

scattering town on a small river" (the Little River not the Connecticut is

meant), was built chiefly of wood, with here and there a brick dwelling

house.

New York, with two or three thousand buildings and from sixteen to

seventeen thousand people in 1760, was very irregular in plan, with

streets which were crooked and exceedingly narrow but generally pretty

well paved, thus adding "much to the decency and cleanness of the place

and the advantage of carriage. " Many of the houses were built in the old

Dutch fashion, with their gables to the street, but others were more

modern, "many of 'em spacious, genteel houses, some being 4 or 5 stories

high, others not above two, of hewn stone, brick, and white Holland tiles,

neat but not grand. " A round cupola capping a square wooden church tower

rising above a few clustering houses was all that marked the town of

Brooklyn, while a ferry tavern and a few houses were all that foreshadowed

the future greatness of Jersey City. Albany was as yet a town of dirty and

crooked streets, with its houses badly built, chiefly of wood, and

unattractive in appearance.

Southward across the river from New York were Elizabeth, New Brunswick,

and Perth Amboy, the last with a few houses for the "quality folk," but "a

mean village, " albeit one of the capitals of the province of New Jersey.

Burlington, the other capital, consisted "of one spacious large street

that runs down to the river, " with several cross streets, on which were a

few "tolerable good buildings," with a courthouse which made "but a poor

figure, considering its advantageous location." Trenton, or Trent Town,

was described in 1749 as "a fine town and near to Delaware River, with

fine stone buildings and a fine river and intervals medows, etc. "

Philadelphia had 2100 houses in 1750 and 3600 in 1765, built almost

entirely of brick, generally "three stories high and well sashed, so that

the city must make (take it upon the whole) a very good figure. " The

Virginia ladies who visited the city were wont to complain of the small

rooms and monotonous architecture, every house like every other. The

streets were paved with flat footwalks on each side of the street and well

illumined with lamps, which Boston does not appear to have had until 1773.

Wilmington on the Delaware was a very young town in 1750, "all the houses

being new and built of brick. " Newcastle, the capital, was a poor town of

little importance. There were but few towns in Maryland. Annapolis, the

capital, was "charmingly situated on a peninsula, falling different ways

to the water . . . built in an irregular form, the streets generally

running diagonally and ending in the Town House, others on a house that

was built for the Governor, but never was finished." This "Governor's

House" afterwards became the main building of St. John's College. A

majority of the residences were of brick, substantially built within brick

walls enclosing gardens in true English fashion.

Across the Potomac was Williamsburg, the capital of Virginia and the seat

of William and Mary College, built partly of brick and partly of wood, and

resembling, it seemed to Lord Adam Gordon, a good country town in England.

Norfolk, which was built chiefly of brick, was a mercantile center, with

warehouses, ropewalks, wharves, and shipyards, while Fredericksburg, at

the head of navigation on the Rappahannock, was constructed of wood and

brick, its houses roofed with shingles painted to resemble state.

Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley was described in 1755 as "a town built

of limestone and covered with slate with which the hills abound. " It was

the center of a settled farming country and its inhabitants enjoyed most

of the necessities but few of the luxuries of life and had almost no

books. It is described as being "inhabited by a spurious race of mortals

known by the appellation of Scotch-Irish. " In all of these towns were one

or more churches, the market house, prison, and pillory, and in the chief

city at the usual place of execution was the gallows of the colony.

The older towns of North Carolina, Edenton, Bath, Halifax, and New Bern,

were all small, and in 1760 were either stationary or declining. Their

houses were built of wood and, except for Tryon's palace at New Bern — an

extravagant structure, considering the resources of the colony — the

public buildings were of no significance. Brunswick, too, was declining

and was but a poor town, "with a few scattered houses on the edge of a

wood, " inhabited by merchants. Wilmington was now rapidly advancing to

the leading place in the province, because of its secure harbor, easy

communication with the back country, accessibility to the other parts of

the colony, fresh water, and improved postal facilities. In 1760 it had

about eight hundred people; its houses, though not spacious, were in

general very commodious and well furnished. Peter du Bois wrote of

Wilmington in 1757: "It has greatly the preference in my esteem to New

Bern . . . the regularity of its streets is equal to that of Philadelphia

and the buildings are in general very good. Many of brick, two or three

stories high with double piazzas, which make a good appearance. "

Charleston, or Charles Town as the name was always written in colonial

times, was the leading city of the South and is thus described by Pelatiah

Webster, who visited it in 1765: "It contains abt 1000 houses with

inhabitants 5000 whites and 20,000 blacks, has

eight houses for religious worship . . . the streets run N. & S. & E. & W.

intersecting each other at right angles, they are not paved, except the

footways within the posts abt 6 feet wide, which are paved with brick in

the principal streets. " According to a South Carolina law all buildings

had to be of brick, but the law was not observed and many houses were of

cypress and yellow pine. Laurens said in 1756 that "none but the better

class glaze their houses. " The sanitary condition of all colonial towns

was bad enough, but the grand jury presentments for Charleston and

Savannah which constantly found fault with the condition of the streets,

the sewers, and necessary houses, and the insufficient scavenging, leave

the impression on the mind of the reader that these towns especially were

afflicted with many offensive smells and odors. The total absence of any

proper health precautions explains in part the terrible epidemics, chiefly

of smallpox, which scourged the colonists in the eighteenth century.

Taking the colonial area through its entire length and breadth, we find

individual houses of almost every description, from the superb mansions of

the Carters in Virginia and of the Vassalls in Massachusetts to the small

wooden frame buildings, forty by twenty feet or thereabouts, "with a shade

on the backside and a porch on the front," and the simple houses of the

country districts or the western frontier, hundreds of which were small,

of one story, unpainted, covered with roughhewn or sawn flat boards,

weather-stained, with few windows and no panes of glass, and without

adornment or architectural taste. One traveler speaks of the small

plantation houses in Maryland as "very bad, and ill contrived, there

furniture mean, their cooks and housewifery worse if possible, "(Eddis.

Letters, 1769-1777.) and another says that an

apartment to sleep in and another for domestic purposes, with a contiguous

storehouse and conveniences for their live stock gratified the utmost

ambition of the settlers in Frederick County. (Birket,

Cursory Remarks, 1750.) Many a colonist north of

the Potomac lived in nothing better than the "crib " or

"block" house which was made of squared logs and roofed with

clapboards. In contrast to the typical square-built houses of New England,

the Dutch along the Hudson and even to the eastward in Litchfield County,

Connecticut, built quaint, low structures which they frequently placed on

a hillside in order to utilize the basement as living rooms for the

family.

The better colonial houses were wainscoted and paneled or plastered and

whitewashed, and the woodwork — trim, cornices, stair railings, and newel

posts — was often elaborately carved. Floors were sometimes of double

thickness and were laid so that "the seam or joint of the upper course

shall fall upon the middle of the lower plank which prevents the air from

coming thro' the floor in winter or the water falling down in summer when

they wash their houses. " Roofs were covered with tile, slate, shingles,

and lead, though much of the last was removed for bullets at the time of

the Revolution. Flat tiles, made in Philadelphia and elsewhere, were used

for paving chimney hearths and for adorning mantels, and firebacks

imported from England were widely introduced. Among the Pennsylvania

Germans wood stoves were generally used, but soft coal brought as ballast

from Newcastle,

THE HALL AT CARTER'S GROVE, VIRGINIA

Photograph by H. P. Cook, Richmond, Va.

Liverpool, and other ports in England and Scotland was also for sale.

Stone coal or anthracite was familiar to Pennsylvania settlers as early as

1763, but until just before the Revolution was not burned as fuel except

locally and on a small scale. Wood was consumed in enormous quantities and

we are told that at Nomini Hall there were kept burning twenty-eight fires

which required four loads of wood a day. (Fithian,

Diary, 1767-1774.)

There were few professional architects, for colonial planters and

carpenters did their own planning and building. What is sometimes called

the "carpenters' colonial style" was often designed on the spot or taken

from Batty Langley's Sure Guide, the Builders' Jewel, or the British

Palladio. Smibert, the painter and paint-shop man of Boston, designed

Faneuil Hall and succeeded in creating a very unsuccessful building

architecturally. The first professional architect in America was Peter

Harrison, who drew the plans for King's Chapel, the Redwood Library, the

Jewish Synagogue, and Brick Market at Newport, yet even he combined

designing with other avocations. In truth there was no great need of

architects in colonial days. Styles did not vary much, certainly not in

New England and the Middle Colonies, and a good

carpenter and builder could do all that was needed. There were scores of

houses in New England similar to Samuel Seabury's rectory at Hempstead, —

a story and a half high in front, with a roof of a single pitch sloping

down to one story in the rear, low ceilings everywhere, four rooms with a

hall on the first floor, a kitchen behind, and three or four rooms on the

second story.

The brick houses were more elaborate and were sometimes built with massive

end chimneys, between which was a steep-pitched roof with dormers and a

walk from chimney to chimney many feet wide. Other houses, made of wood as

well as brick, had hipped roofs with end chimneys or roofs converging to a

square center and a railed lookout. All the nearly 150 colonial houses

still standing in Connecticut conform to a common type, though they differ

greatly in the details of their paneling, mantels, cupboards, staircases,

closed or open beamed ceilings, fireplaces, and the like. Some had slave

quarters in the basement, others under the rafters in what was called in

one instance "the Black Hole. " Many of even the better houses were

unpainted inside and out; many had paper, hung or tacked (afterwards

pasted) on the walls; and in a few noteworthy cases in New England the

chimney breasts were adorned with paintings. The floors were usually bare

or covered with matting; rugs were used chiefly at the bedside, but

carpets were rare.

Philadelphia, which was famous for the uniformity of its architecture,

must have contained in 1760 many houses of the style of that built for

Provost Smith of the College of Philadelphia. In addition to a garret this

dwelling had three stories respectively eleven, ten, and nine feet high.

The brick outside walls were fourteen inches thick and the partition

walls, of the same material, nine inches. There were windows and window

glass, heavy shutters, a plain cornice, cedar gutters and pipes. The

woodwork, inside and out, was painted white, and all the rooms were

plastered. No mention is made of white marble steps, but there may have

been such, for no Philadelphia house was complete without them.

The Southern houses, both on the plantations and in the towns, varied so

widely in their style of architecture that no single description will

serve to characterize all. Such buildings as the Governor's palace at

Williamsburg, Tryon's palace at New Bern, and the Government House at

Annapolis were handsome buildings provided with conveniences for

entertainment, and that at New Bern contained rooms for the gathering of

assembly and council. The most representative Southern plantation house

was of brick with wings, the kitchens on one side and the carriage house

on the other, sometimes attached directly to the central mansion and

sometimes entirely separate or connected only by a corridor. In the

Carolinas and Georgia, however, there were many rectangular houses without

wings, built of wood or brick, with rooms available for summer use in the

basement. The roof was often capped with a cupola and commanded a wide

prospect.

The dwelling houses of Charleston were among the most distinctive and

quaint of all colonial structures. Some of them were divided into

"tenements" quite unlike the tenements and flats of the present day, for,

in addition to its independent portion of the house, each family had its

own yard and garden. Overseers' houses were as a rule small, about twenty

feet by twelve, with brick chimneys and plastered rooms. A typical

Savannah house had two stories, with a handsome balcony in front and a

piazza the whole length of the building in the rear, with a bedroom at one

end and a storehouse at the other. The dining room was on the second

floor, and everywhere, for convenience and comfort, were to be found

closets and fireplaces. Among the gentry in a country where storms were

frequent, electrical rods were in use, and in 1763 one Alexander Bell of

Virginia advertised a machine for protecting houses from being struck by

lightning, though what his contrivance was we do not know.

The town halls and courthouses generally followed English models, with

public offices and assembly rooms on the upper floor and a market and

shops below. The Southern courthouses were at first built of wood and

later of brick, with shingled roofs, heavy planked floors, and

occasionally a cupola or belfry. Those of the eighteenth century either

included the prison and pillory or were connected with them. The

inadequacy of jail accommodation was a cause of constant complaint. Not

only did grand juries and newspapers point out the need of quarters so

arranged that debtors, felons, and negroes should not be thrown together,

but the occupants themselves protested against the nauseating smells and

odors. In some of the prisons, it is true, a separate cage was provided

for the negroes, and in North Carolina prison bounds, covering some six

acres about the building, were laid out for the use of the prisoners, an

arrangement which was not abolished till the nineteenth century.

In all the cities of the North and South stores and shops were to be

found, occupying the first floor, while the family lived in the rooms

above. As a rule, a shop meant a workshop where articles were made, a

store a storehouse where goods were kept. But in practice usage varied, as

"shop" was in common use in New England for any place where things were

sold, and "store" was the usual term in Philadelphia and the South. An

apprentice writing home to England in 1755 and trying to explain the use

of the terms said: "Stores here [in Virginia] are much like shops in

London, only with this difference, the shops sell but one kind or species

of wares and stores all kinds. " Some of these stores, particularly in

Maryland and Virginia, were located away from the urban centers, in the

interior near the courthouses at the crossroads, along the rivers at the

tobacco inspection houses, or wherever else men congregated for business

or public duty. They were often controlled by English or Scottish firms

and managed by agents sent to America. They received their supplies from

Great Britain and they sold, for credit, cash, or tobacco, almost

everything that the neighborhood needed.

Varied as were the architectural features of colonial houses, they were

paralleled by an equal diversity in the household effects with which these

dwellings were equipped. It is impossible even to summarize the

information given in the thousands of extant wills, inventories, and

invoices which reveal the contents and furnishings of these houses.

Chairs, bureaus, tables, bedsteads, buffets, cupboards, were in general

use. They were made of hickory, pine, maple, cypress, oak, and even

mahogany, which began to be used as early as 1730. From the meager dining

room outfit of only one chair, a bench, and a table, all rough and

homemade, we pass to the furnishings of the richer merchants in the

Northern cities and of the wealthier planters in Maryland, Virginia, and

the Carolinas. But we cannot take the establishments of Wentworth,

Hancock, Vassall, Faneuil, Cuyler, Morris, Carter, Beverley, Manigault, or

Laurens as typical of conditions which prevailed in the majority of

colonial homes. Some people had silver plate, mahogany, fine china, and

copper utensils; others owned china, delftware, and furniture of plain

wood, with perhaps a few silver spoons, a porringer, and an occasional

mahogany chair and table; still others, and these by far the largest

number, used only pewter, earthenware, and wooden dishes, with the simpler

essentials, spinning wheel, flatirons, pots and kettles, lamps and

candlesticks, but no luxuries. There was in addition, of course, the class

of the hopelessly poor, but it was not large and need not be reckoned with

here.

The average New England country household was a sort of self-sustaining

unit which depended little on the world beyond its own gates. Its

equipment included not only the usual chairs, beds, tables, and kitchen

utensils and tableware but also shoemakers' tools and shoe leather —

frequently tanned in the neighborhood and badly done as a rule, —

surgeon's tools and apothecary stuff, salves and ointments, branding

irons, pestle and mortar, lamps, guns, and perhaps a sword, harness and

fittings, occasionally a still or a cider press, and outfits for

carpentering and blacksmithing. The necessary utensils for use in the

household or on the farm were more important than upholstery, carved

woodwork, fine linen, or silver plate. Everywhere there were hundreds of

families which concerned themselves little about ornament or design. They

had no money to spend on non-essentials, still

less on luxuries, and from necessity they used what they already possessed

until it was broken or worn out; then, if it were not entirely useless,

they repaired and patched it and went on as before. Economy and

convenience made them use materials that were close at hand; and in many

New England towns a familiar figure was the wood turner, who made plates

and other utensils out of " dish-timber " as it was called, a white wood

which was probably poplar or linden, but not basswood. Yet economical as

these people were, even the unpretentious households possessed an

abundance of mugs and tankards, which suggest their one indulgence and

their enjoyment of strong drink.

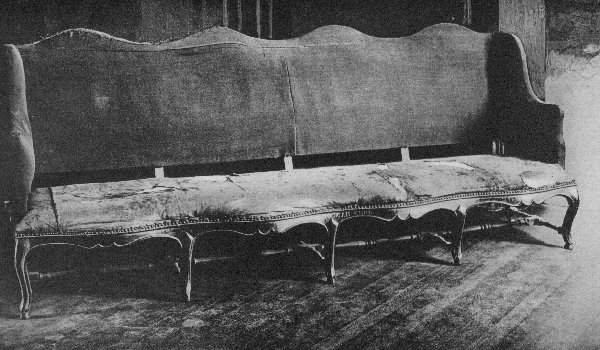

JOHN HANCOCK'S SOFA

In Pilgrim Hall. Plymouth. Mass.

As conditions of life improved and wealth increased, the number of those

who were able to indulge in luxuries also increased. The period after 1730

was one of great prosperity in the colonies owing to the enlarged

opportunities for making money which trade, commerce, and markets

furnished. Though it was also a time of higher prices, rapid advance in

the cost of living, and general complaint of the inadequacy of existing

fees and salaries, those who were engaged in trade and had access to

markets were able to indulge in luxuries which were unknown to the earlier

settlers and, which remained unknown to those living in the rural

districts and on the frontier.

In the Northern cities and on Southern plantations costly and beautiful

household furnishings appeared: furniture was carved and upholstered in

leather and rich fabrics; tables were adorned with silver, china, and

glassware; and walls were hung with expensive papers and decorated with

paintings and engravings — all brought from abroad. A house thus equipped

was not unlikely to contain a mahogany dining table capable of seating

from fourteen to twenty persons, and an equal number of best Russia

leather chairs, two of which would be arm or "elbow" chairs, double

nailed, with broad seats and leather backs. Washington, for example, in

1757 bought "two neat mahogany tables 4½ feet square when spread and to

join occasionally," and "1 doze neat and strong mahogany chairs, " some

with "Gothick arched backs," and one "an easy chair on casters. " About

the rooms were pieces of mahogany furniture of various styles, tea tables,

card tables, candle stands, settees, and "sophas." On the walls, which

were frequently papered, painted in color, or stenciled in patterns, hung

family portraits painted by artists whose names are in many cases unknown

to us, and framed pictures of hunting scenes, still life, ships, and

humorous subjects, among which the engravings of Hogarth were always prime

favorites. On the chimney breast, above the mantel, there was sometimes a

scene or landscape, either painted directly on the wall itself or executed

to order on canvas in England and brought to America. There were eight-day

clocks and mantel clocks, and sconces, carved and gilt, upstairs and down.

In the cupboard and on the sideboard would be silver plate in great

variety and sets of best English china, ivory-handled knives and forks,

glass in considerable profusion, though glassware, as a rule, was not much

used, diaper tablecloths and napkins, brass chafing dishes, and steel

plate warmers. There was always a centerpiece or epergne of silver, glass,

or china.

In the bedrooms were pier glasses and bedsteads in many forms and colors,

of mahogany and other woods. Frequently there were four-posters, with

carved and fluted pillars and carved cornices or " cornishes, " as they

were generally spelled. The bedsteads were provided with hair mattresses

and feather beds, woolen blankets, and linen sheets, and were adorned with

silk, damask, or chintz curtains and valances. Russian gauze or lawn was

used for mosquito nets, for mosquitoes were a great pest to the colonists.

On the large plantations there was to be found a great variety of utensils

for kitchen, artisan, and farm use, most of which were brought from

England, but some, particularly iron pots, axes, and scythes, from New

England. For the kitchen there were hard metal plates, copper kettles and

pans, pewter dishes in large numbers, chiefly for servants' use, yellow

metal spoons, stone bottles, crocks, jugs, mugs, butter pots, and heavy

utensils in iron for cooking purposes. For the farm there were

grindstones, saws, files, knives, axes, adzes, planes, augurs, irons, hay

rakes, carts, forks, reaping hooks, wheat sieves, spades, shovels,

watering pots, plows, plowshares, and moldboards, harness and traces,

harrows, ox chains, and scythes.

The farmer was thus provided with all the implements necessary for mowing,

clearing underbrush, and cradling wheat, and all the other essential

activities of an agricultural life. A wheel plow is mentioned as early as

1732, and in 1748 James Crokatt, an influential Charlestonian in England,

sent over a plow designed to weed, trench, sow, and cover indigo, but of

its construction we unfortunately know nothing. The colonists

usually imported such articles as millstones, as large as

forty-eight inches in diameter and fourteen inches thick, frog spindles

and other parts for a tub mill or gristmill, hand presses, with lignum-vitæ

rollers for cider, copper stills with sweat worms and a capacity as high

as sixty gallons, vats for indigo, and pans for evaporating salt. For

fishing there were plenty of rods, lines, hooks, seines with leads and

corks, and eel pots. In addition to this varied

equipment, nearly all the plantations had outfits for coopering, tanning,

shoemaking, and other necessary occupations of a somewhat isolated

community. Separate buildings were erected in which this artisan work was

done, not only for the planter himself but also for his neighbors. Indeed

the returns from this community labor constituted an important item in the

annual statement of many a planter's income.

Back to: Colonial Folkways