Town And Country

The tilling of the soil absorbed the energies of not less than

nine-tenths of the colonial population. Even those who by occupation were

sailors, fishermen, fur traders, or merchants often gave a part of their

time to the cultivation of farms or plantations. Land hunger was the

master passion which brought the men of the seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries across the sea and lured them on to the frontier. Where hundreds

sought for freedom of worship and release from political oppression,

thousands saw in the great unoccupied lands of the New World a chance to

make a living and to escape from their landlords at home. To obtain a

freehold in America was, as Thomas Hutchinson once wrote of New England,

the "ruling purpose" which sent colonial sons with their cattle and

belongings to some distant frontier township, where they would thrust back

the wilderness and create a new community. Throughout the whole of the

colonial period this migration westward in quest of land, whether overseas

or through the wilderness, whether from New England or Old England or the

Continent, continued at an accelerating pace. The Revolutionary troubles,

of course, brought it temporarily to a standstill.

In New England — outside of New Hampshire, where the Allen family had a

claim to the soil that made the people of that colony a great deal of

trouble — every individual was his own proprietor, the supreme and

independent lord of the acres he tilled. But elsewhere the ultimate title

to the soil lay in the hands of the King or of such great proprietors as

the Baltimores and the Penns, to whom grants had been made by the Crown.

The colonist who obtained land from King or proprietor was expected to pay

a small quitrent as a token of the higher ownership. The quitrent was not

a real rent, proportionate to the actual value of the acres held; it was

never large in amount nor burdensome to the settler; and it was rarely

increased, whether the price of land rose or fell. The colonists never

liked the quitrent, however, and in many instances resolutely refused to

pay it, so that it became in time a cause of friction and a source of

discontent which played some part in arousing in America the desire for

independence. Once when the people of North Carolina complained of the way

their lands were doled out, the Governor replied that if they did not like

the conditions they could give up their lands, which after all were the

King's and not theirs. It was a small thing, this quitrent, but it touched

men's daily lives a thousand times more often than did some of the larger

grievances to which the Revolution has been ascribed.

The towns of New England were compact little communities, favorably

situated by sea or river, and their inhabitants were given over in the

main to the pursuit of agriculture. Even many of the seaports and fishing

villages were occupied by a folk as familiar with the plow as with the

warehouse, the wharf, or the fishing smack, and accustomed to supply their

sloops and schooners with the produce of their own and their neighbors'

acres. Life in the towns was one of incessant activity. The New

Englander's house, with its barns, outbuildings, kitchen garden, and back

lot, fronted the village street, while near at hand were the meetinghouse

and schoolhouse, pillories, stocks, and signpost, all objects of constant

interest and frequent concern. Beyond this clustered group of houses

stretched the outlying arable land, meadows, pastures, and woodland, the

scene of the villager's industry and the source of his livelihood. Thence

came wheat and corn for his gristmill, hay and oats for his horses and

cattle, timber for his sawmill, and wood for the huge fireplace which

warmed his home. The lots of an individual owner would be scattered in

several divisions, some near at hand, to be reached easily on foot, others

two or more miles distant, involving a ride on horseback or by wagon.

While most of the New Englanders preferred to live in neighborly fashion

near together, some built their houses on a convenient hillside or fertile

upland away from the center. Here they set up "quarters" or "corners"

which were often destined to become in time little villages by themselves,

each the seat of a cow pound, a chapel, and a school. Sometimes these

little centers developed into separate ecclesiastical societies and even

into independent towns; but frequently they remained legally a part of the

original church and township, and the residents often journeyed many miles

to take part in town meeting or to join in the social and religious life

of the older community.

The New Englander who viewed for the first time the list of his allotments

as entered in the town book of land records had

the novel sensation of knowing that to all intents and purposes they were

his own property, subject of course to the law of the colony, which he

himself helped to make through his representatives in the Assembly;

subject, too, more remotely, to the authority of the King across the sea.

But the King did not often bother him. He could do with his land much as

he pleased: sell it if need be, leave it to his children by will, or add

to it by purchase. The New Englander loved a land sale as he loved a horse

trade and any dicker in prices; but he had a stubborn sense of justice and

a regard for the letter of the law which often drove him to the courts in

defense of his land claims. Probably a majority of the cases which came

before the New England courts in colonial times had to do with land. Yet

there was little accumulation of large properties or landed estates, for

such were contrary to the Puritan's ideas of equality. Jonathan Belcher,

later a Governor of Massachusetts, had in eastern Connecticut a manor

called Mortlake, on which were a few un-enterprising tenants, holding their

land for a money rental. There are other instances of lands let out in a

similar manner on limited leases, but the number was not large, for, as

Hutchinson said, the Puritan's ruling passion was for a freehold and not a

tenancy, and "where there is one farm in the hands of a tenant, " he

added, "there are fifty occupied by him who has the fee of it."

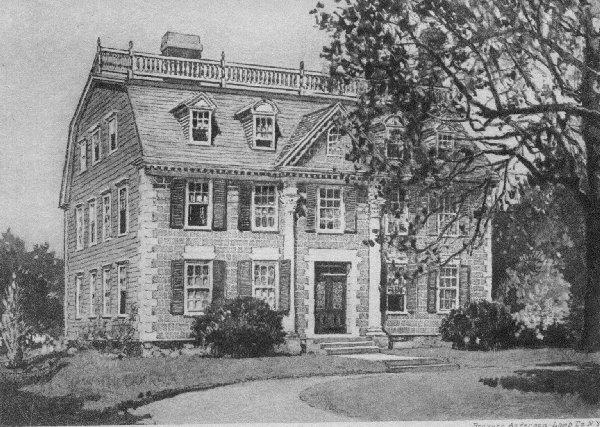

THE PEABODY MANSION, DANVERS, MASS.

One of the best specimens of New England Colonial domestic architecture.

Built by "King" Hooper, of Marblehead, about 1754.

Outside New England there was greater variety of landholding and

cultivation. The Puritan traveler journeying southward through the Middle

Colonies must have seen many new and unfamiliar sights as he looked over

the country through which he passed. He would have found himself entirely

at home among the towns of Long Island, Westchester County, and northern

New Jersey, and would have discovered much in the Dutch villages about New

York and up the Hudson that reminded him of the closely grouped houses and

small allotments of his native heath. But had he stopped to investigate

such large estates as the Scarsdale, Pelham, Fordham, and Morrisania

manors on his way to New York, or turned aside to inspect the great

Philipse and Cortlandt manors along the lower Hudson, or the still greater

Livingston, Claverack, and Rensselaer manors farther north, he would have

seen wide acres under cultivation, with tenants and rent rolls and other

aspects of a proprietary and aristocratic order. Had he made further

inquiries or extended his observations to the west and north of the

Hudson, he would have come upon grants of thousands of acres lavishly

allotted by governors to favored individuals. He would then have realized

that the division of land in New York, instead of being fairly equal as in

New England, was grossly unequal. On the one hand were the petty acres of

small farms surrounding the towns and villages; on the other were such

great estates as Morrisania and Rensselaerwyck, where the farmers were not

freeholders but tenants, and where the proprietors could ride for miles

through arable land, meadow, and woodland, without crossing the boundaries

of their own territory. If the traveler had been interested, as the

average New England farmer was not, in the deeper problems of politics, he

would have seen, in this combination of small holdings with large, one

explanation, at least, of the differences in political and social life

that existed between New England and New York.

What the traveler might have noticed in New York, he would have found

repeated in a lesser degree in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. There, too, he

would have seen large properties, such as the great tracts set apart for

the proprietors and still awaiting sale and distribution, and such

extensive estates as that of Lewis Morris, known as Tinton Manor, near

Shrewsbury in East Jersey, and the proprietary manors of the Penns at

Pennsbury on the Delaware and at Muncy on the Susquehanna. But there were

also thousands of small fields belonging to the Puritan and Dutch settlers

at Newark, Elizabeth, Middletown, Bergen, and other towns in northern New

Jersey, and a constantly increasing number of somewhat larger farms in the

hands of the Germans and Scotch-Irish in the back counties of

Pennsylvania. The traveler would have noticed also, as he rode from Perth

Amboy to Bordentown or Burlington, or from New Brunswick to Trenton, that

central New Jersey was a flat, unoccupied country, with scarcely a

mountain or even a hill in forty miles, that the sort of towns he was

familiar with had entirely disappeared, and that along the highway to the

Delaware and even from Trenton to Philadelphia, the country had only an

occasional isolated farmstead. He would have met with no plantations in

the southern sense of the word, with almost no tenancies like those at

Rensselaerwyck, and with only a few compact settlements, such as the large

towns of Trenton, Bordentown, Burlington, Philadelphia, Germantown, and

Lancaster, and the loosely grouped villages of the Germans, where the

lands were held in blocks and the houses of the settlers were more

scattered than among the Puritans. He would have learned also that, in

Pennsylvania particularly, the needs of the proprietors, the demands of

the colonists, and the character of the crops were leading to frequent

sales and to the division of large estates into small and manageable f

arms.

What probably would have interested the New Englanders as much as anything

else was the interdependence of city and country which was frequently

manifested along the way. Unlike the Puritans, to whom countryseats and

summer resorts were unknown and trips to mountain and seashore were

strictly matters of necessity or business, the townfolk of the Middle

Colonies residing in New York, Burlington, and Philadelphia had country

residences, not mere cottages for makeshift housekeeping but substantial

structures, often of brick, well furnished within and surrounded by

grounds neatly kept and carefully cultivated. There were many stately

"gentlemen's seats," belonging to the gentry of New York, between

Kingsbridge and the city and on Long Island, for what is now Greater New

York was then for the most part open country, hilly, rocky, and heavily

wooded, interspersed here and there with houses, farms, fields, groves,

and orchards of fruit trees, and threaded by roads, some good and some

bad. Philip Van Cortlandt had his country place six miles, as he then

reckoned it, from the city. Here at Bloomingdale, a village in a sparsely

settled neighborhood — now the uptown shopping district of New York,

somewhat north of the present public library — he was wont to send Mrs.

Van Cortlandt and his "little family" to spend "the somer season." The

Burlington merchants had their country houses near the Delaware on the

high ground stretching along the river and back toward the interior. On

the other hand, Philadelphia merchants, mayors, and provincial governors,

whose city life was confined to half a dozen streets running parallel to

the Delaware, had their country residences often twelve or fifteen miles

away, sometimes in West Jersey, but more often in Pennsylvania itself,

adjacent to the familiar and well-trodden highways. These roads, which

radiated northwest and south from the river, formed arteries of supply for

the markets and ships along the docks and, during certain times and

seasons, afforded means of social intercourse between the business of the

counting house in town and the pleasure of the

dining hall and assembly room in the country.

To the Southerner, on the other hand, who passed observantly northward and

viewed with discernment the country from Maryland to that "way down east"

land of Maine which was as yet little more than a narrow fringe of rocky

coast between the Piscataqua and the Kennebec, all these conditions of

housing and cultivation must have seemed to a large extent strangely novel

and unfamiliar. The Southerner was not used to small holdings and closely

settled towns; his eye was accustomed to range over wide stretches of land

filled with large estates and plantations. The clearings to which he was

accustomed, though often little more than a third of the whole area,

consisted of great fields of tobacco, grain, rice, and indigo, and

presented an appearance essentially unlike that of the small and scattered

lots and farms of the New England towns. He was unacquainted with the

self-centered activity of those busy northern communities or the narrow

range of petty duties and interests that filled the day of the Puritan

farmer and tradesman. Were he a landed aristocrat of Anne Arundel or

Talbot county in Maryland, he would himself have possessed an enormous

amount of property consisting of scattered tracts in all parts of the

province, sometimes fifteen or thirty thousand acres in all. Many of these

estates he was accustomed to speak of as manors, though the peculiar

rights which distinguished a manor from any other tract of land early

disappeared, and the manor in Maryland and Virginia, as elsewhere, meant

merely a landed estate. But the name undoubtedly gave a certain

distinction to the owner and probably served to hold the lands together in

spite of the prevailing tendency in Maryland to break up the estates into

small, convenient farms. Doughoregan Manor of the Carrolls with its ten

thousand acres, for instance, remains undivided to this day.

By the wealthy Virginian the term manor was used much less frequently than

it was in Maryland, while in the Carolinas and Georgia it was not used at

all. In Virginia, even though the great plantation with its appendant

farms and quarters in different counties could be reached often only after

long and troublesome rides over bad roads through the woods, the estate

was generally kept intact. Though land was frequently leased and overseers

were usually employed to manage outlying properties, the habit of

splitting up estates into small farms was much less common than it was in

Maryland. Councilman Carter owned, we are told, some sixty thousand acres

situated in nearly every county in Virginia, six hundred negroes, lands in

the neighborhood of Williamsburg, an "elegant and spacious" house in the

same city, stock in the Baltimore Iron Works, and several farms in

Maryland. It was not at all uncommon for men in one town or colony to own

land in another, for even in New England the owners of town lands were not

always residents of the town in which the lands were situated.

It would be a mistake, however, to think of Maryland and Virginia as

covered only by great plantations with swarms of slaves and lordly

mansions. In both these Southern Colonies there were hundreds of small

farmers possessing single grants of land upon which they had erected

modest houses. Many of these farmers rented lands of the planter under

limited leases and paid their rents in money, or probably more often in

produce, labor, and money, as did the tenants of William Beverley of

Beverley Manor on the Rappahannock. As many of the large estates in

Maryland could not be worked by the owner, the practice arose of renting

some and of breaking up others for sale. In this way there came into

existence numbers of middle-class landholders, who formed a distinctly

democratic element both in Maryland and Virginia. They cultivated small

plantations ranging from 150 to 500 acres, not more than a third of which

was improved even by 1760. Daniel Dulaney, the famous lawyer of Annapolis

who had made his money in tidewater enterprises, bought land in central

Maryland, which he rented out to Germans from Pennsylvania and thus became

a land promoter and town builder on an extensive scale.

Though no such mania for land speculation seized upon the Virginia

planters, they were equally zealous in acquiring properties for themselves

beyond the "fall line" to the west, and some of them endeavored to add to

their wealth by promoting the building of towns. It was in 1745 that

Dulaney laid out the town of Frederick as a shrewd business enterprise.

Eight years earlier, the second William Byrd, one of the farseeing men of

his time, had advertised for sale in town lots his property near the

inspection houses at Shoccoe's. This was the beginning of Richmond, the

capital of Virginia. Less successful was Richard Randolph when, in1739, he

tried to attract purchasers to his town of Warwick, in Henrico County,

modeled after Philadelphia, with a hundred lots at ten pistols each, a

common, and all conveniences for trade thrown into the bargain. But the

only really important towns in these colonies during the colonial period

were Annapolis and Williamsburg. In these towns many of the planters had

houses which they occupied during the greater part of the year or at any

rate when the Assembly was in session and life was gay and festive. Such

other centers of population as Baltimore, Frederick, Hagerstown, Norfolk,

Falmouth, Fredericksburg, and Winchester played little part in the life of

the colonies except as business communities.

As the Albemarle region of North Carolina was settled from Virginia, the

plantation and the tobacco field were introduced together, and along the

sound and its rivers landed conditions arose similar in some respects to

those in Virginia. The word "f arm " was not used, but the term

"plantation" was employed to include anything from the great estates of

such men as Seth Sothell, one of the "true and absolute proprietors," and

Philip Ludwell, Governor, to the small holdings of less important men, who

received grants from the proprietors and later from the Crown in amounts

not exceeding a square mile in extent. Though as a rule the holdings in

Albemarle were smaller than elsewhere in the South and the conditions of

life were simpler and less elaborate, the farmers were still freeholders,

not tenants. The whole of this section remained less developed in

education, religious organization, and wealth than other plantation

colonies, and such towns as it had, Edenton, Bath, New Bern, and Halifax,

were smaller and less conspicuous as social and business centers than were

Annapolis, Williamsburg, and Charleston. Governor Johnston, who was

largely responsible for the transfer of government from New Bern to the

Cape Fear River, said in 1748: "We still continue vastly behind the rest

of the British settlements both in our civil constitution and in making a

proper use of a good soil and an excellent climate."

It was an important event in the history of North Carolina when Maurice

and Roger Moore of South Carolina in 1725 selected a site on the south

bank of the Cape Fear River, ten miles from its mouth, and laid out the

town of Brunswick. With the transfer of the colony to the Crown in 1729,

the settlement increased and prospered, lands were taken up on both sides

of the river from its mouth to the upper

branches, and plantations were established which equaled in size and

productiveness all but the very largest in Maryland, Virginia, and South

Carolina. At first many of the planters purchased lots in Brunswick, but

afterwards transferred their allegiance to Wilmington on the removal to

that town of the center of social and political life. No people in the

Southern Colonies were more devoted than they to their plantation life or

took greater pride in the beauty and wholesomeness of their country. They

raised corn and provisions, bred stock — notably the famous black cattle

of North Carolina — and made pitch, tar, and turpentine from their

lightwood trees, and these, together with lumber, frames of houses, and

shingles, they shipped to England and to the West Indies. The Highlanders

who settled at Cross Creek at the head of navigation above Wilmington

brought added energy and enterprise to the colony and developed its trade

by shipping the products of the back country down the river and by taking

in return the manufactures of England and the products of the West Indies.

Some of them built at Cross Creek dwellings and warehouses, mills and

stores, and set up plantations in the neighborhood; others, among whom

were a few Lowland Scots, spread farther afield and bought lands even in

the Albemarle region. To this section, after it had stagnated for thirty

years, they brought new interests and prosperity by opening communication

with Norfolk, in Virginia, as a port of entry and a market for their

staples. They thus prepared the way for a promising agricultural and

commercial development, which unfortunately was checked and for the moment

ruined by the unhappy excesses and hostilities of the Revolutionary

period.

South of Cape Fear lay Georgetown, Charleston, and Savannah, centers of

plantation districts chiefly on the lower reaches of the rivers of South

Carolina and Georgia. These plantations were characterized by a close

union between town and country. South Carolina differed from the other

colonies in that a considerable portion of her territory had been laid out

in baronies under that clause of the Fundamental Constitutions which

stipulated the number of acres to be set apart for colonists bearing

titles of nobility. Thus it was provided that 48,000 acres should be the

portion for a landgrave, 24,000 for a cacique, and 12,000 for a baron.

Many colonists who bore these titles took up lands at various times and in

varying amounts, but their properties, which

probably never exceeded 12,000 acres in a single grant, differed in no way

but name from any other large plantations. The most famous of the

landgraves were Thomas Smith, who was Governor in 1695, and his son, the

second landgrave, whose mansion of Yeomans Hall on the Cooper River, with

all its hospitality, gayety, romance, and tragedy, has been graphically

though somewhat fancifully pictured by Mrs. Elizabeth A. Poyas in The

Olden Time of Carolina.

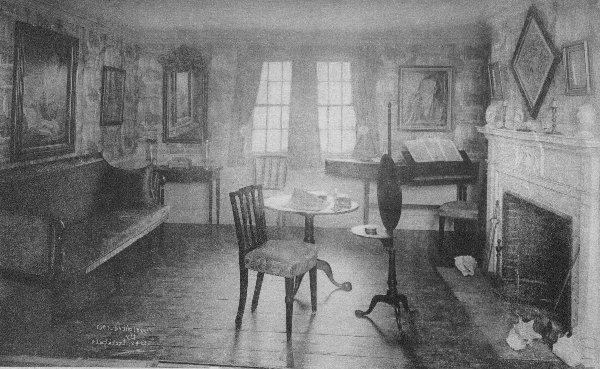

A NEW ENGLAND PARLOR OF ABOUT 1800

Showing carved wooden mantel, combined table and tire screen, and

spinet. In the Essex Institute, Salem, Mass.

Most of the plantations of South Carolina and Georgia were smaller than

those in Maryland and Virginia. A single tract rarely exceeded 2000 acres,

and an entire property did not often include more than 5000 acres. These

estates seem to have been on the whole more compact and less scattered

than elsewhere. They lay contiguous to each other in many instances and

formed large continuous areas of rice land, pine land, meadow, pasture,

and swamp. Upon such plantations the colonists built substantial houses of

brick and cypress, generally less elaborate than those in Virginia,

particularly when they were described as of "the rustic order." There were

also tanyards, distilleries, and soap-houses, as well as all facilities

for raising rice, corn, and later indigo. At first the chief staple on

these plantations was rice; but the introduction of indigo in 1745, with

its requirement of vats, pumps, and reservoirs, and its plague of refuse

and flies, though of great significance in restoring the prosperity of the

province, gave rise to new and in some respects less agreeable conditions.

The plantations were also supplied with a plentiful stock of cattle and

the necessary household goods and furnishings. The following detailed

description of William Dry's plantation on the Cooper River, two miles

above Goose Creek, is worth quoting. The estate, which fronted the high

road, is described as

having on it a good brick dwelling house, two brick store houses, a brick

kitchen and washhouse, a brick necessary house, a barn with a large brick

chimney, with several rice mills, mortars, etc., a winnowing house, an

oven, a large stable and coach-house, a cooper's shop, a house built for a

smith's shop; a garden on each side of the house, with posts, rails, and

poles of the best stuff, all planed and painted and bricked underneath; a

fish pond, well stored with perch, roach, pike, eels, and catfish; a

handsome cedar horse-block or double pair of stairs; frames, planks, etc.,

ready to be fixed in and about a spring within three stones' throw of the

house, intended for a cold bath and house over it; three large dam ponds,

whose tanks with some small repairs will drown upwards of 100 acres of

land, which being very plentifully stored with game all the winter season

affords great diversion; an orchard of very good apple and peach trees, a

corn house and poultry house that may with repairing serve some years

longer, a small tenement with a brick chimney on the other side of the

high road, fronting the dwelling house, and at least 400 acres of the land

cleared, all except what is good pasture, and no part of the tract bad,

the whole having a clay foundation and not deep, the great part of it

fenced in, and upwards of a mile of it with a ditch seven feet wide and

three and a half deep.

Most of the South Carolina planters had their town houses and divided

their time between city and country. They lived in Charleston, Georgetown,

Beaufort Town, and Dorchester, but of these Charleston was the Mecca

toward which all eyes turned and in which all lived who had any social or

political ambitions. Attempts were made in the eighteenth century, in this

colony as elsewhere, to boom land sites for the erecting of towns on an

artificial plan. In 1738, the second landgrave, Thomas Smith, tried to

start a town on his Win-yaw tract near Georgetown. He laid out a portion

of the land along the bluff above the Winyaw River in lots, offered to

sell some and to give away others, and planned to provide a church, a

meetinghouse, and a school. But this venture failed; and even the more

successful attempt to build up Willtown about the same time, although lots

were sold and houses built and occupied, eventually came to nothing. The

story of some of these dead towns of the South, whether promoted by

natives or settled by foreigners, has been told only in part and forms an

interesting chapter in colonial history.

In all the colonies, indeed, the eighteenth century saw a vast deal of

land speculation. The merchants and shopkeepers in most of the large towns

acted as agents and bought and sold on commission. Just as George Tilly,

merchant and contractor of Boston, advertised good lots for sale in 1744,

so John Laurens, Robert Hume, and Benjamin Whitaker in Charleston a little

later were dealing in houses, tenements, and plantations as a side line to

their regular business as saddlers and merchants. In the seventies the

sale of land had become an end in itself, and one Jacob Valk advertised

himself as a "Real and Personal Estate Dealer." The meaning of the change

is clear. Desirable lands in the older settlements were no longer

available except by purchase, and men were already looking beyond the

"fall line" and the back country to the ungranted lands of the new

frontier in the farther West.

Back to: Colonial Folkways